Net neutrality is the simple principle that all information be treated equally when being delivered over a network. While net neutrality opponents like to pretend this was a new concept when Tom Wheeler’s FCC adopted the open internet rules in 2015, net neutrality has been a tradition in the U.S. for over 150 years.

In fact, net neutrality was the fundamental principle guiding communications networks in the U.S. until recently. Furthermore, if it were not for the ISP and cable TV lobby, net neutrality would have never been a contentious issue.

The History of Net Neutrality

Since this is a bit of a long read, the history of net neutrality is also discussed in the episode of the Grounded Reason Podcast linked below.

The current FCC Chairman, Ajit Pai, has declared war on net neutrality. He is attempting to abolish the 2015 rules that set the Internet back to its natural state after a brief hijacking at the hands of lobbyists. The rules Chairman Pai want to erase are as follows:

- No Blocking: broadband providers may not block access to legal content, applications, services, or non-harmful devices.

- No Throttling: broadband providers may not impair or degrade lawful Internet traffic on the basis of content, applications, services, or non-harmful devices.

- No Paid Prioritization: broadband providers may not favor some lawful Internet traffic over other lawful traffic in exchange for consideration of any kind—in other words, no “fast lanes.” This rule also bans ISPs from prioritizing content and services of their affiliates.

These rules are not “a power grab” or a “regulatory reach” as Pai and the ISP lobby is fond of saying. In fact, they are rooted in the earliest forms of electronic communication.

The U.S. Federal Pacific Telegraph Act of 1860

Much like the Internet has connected cultures across the globe, the railroad, and telegraph connected people living in cities all across the United States in the 19th century. Our American ancestors knew companies controlling the means of transporting goods and information would have a near divine power over the market. Therefore, the first utterance of net neutrality occurs in the Pacific Telegraph Act of 1860. It reads:

“messages received from any individual, company, or corporation, or from any telegraph lines connecting with this line at either of its termini, shall be impartially transmitted in the order of their reception.”

Americans recognized the importance of separating the content from the carrier with respect to regulation over 150 years ago. Allowing carriers to prioritize distribution of goods and information essentially allows them to pick the winners and the losers in the industries they provide carriage.

Regulators used the designation “common carrier” for carriers that indiscriminately provide services to the public. This concept has its roots in English common law. While many court decisions relegated railroads in the U.S. to common carrier status, it wasn’t until 1897 when they were designated common carrier by the Interstate Commerce Commission.

The Communications Act of 1934

Two decades later Alexander Graham Bell patented the telephone in 1876 and started American Bell, which eventually became American Telephone and Telegraph Company (AT&T)

As other forms of communication came into use, like the telephone and the radio, Congress passed laws specifically relating to the communications medium. For example, the Mann-Elkins Act of 1910 applied to the telephone, while radio communication was governed under the Radio Act of 1927.

In the 1930’s, the government began to realize that the principles of electronic communication were similar regardless of the technology. Therefore, a new regulatory body titled the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) formed under the Communications Act of 1934. From that point forward, the FCC regulated electronic communications in the US.

The 1934 act defined communications technology as a public good. The stated goal of the act was to have broadcasting and telephone technologies regulated the same way the former Interstate Commerce Commission regulated railways; as common carriers.

The Communications Act of 1934 defined common carriers as follows:

(10) COMMON CARRIER.–The term ”common carrier” or ”carrier” means any person engaged as a common carrier for hire, in interstate or foreign communication by wire or radio or in interstate or foreign radio transmission of energy, except where reference is made to common carriers not subject to this Act; but a person engaged in radio broadcasting shall not, insofar as such person is so engaged, be deemed a common carrier.

Notice how the law explicitly differentiates between the people broadcasting as content providers and the transmission mechanism carrying the signal.

Cable TV and The Internet

In the 60’s and 70, the U.S. government developed packet switching networks such as ARPANET, which later became “the internet.” In the 80’s the internet became open for public and commercial use. The U.S. government relinquished any stake in the Internet to the public in 1995.

At this time, access to The Internet was provided over the existing telecommunications infrastructure. Therefore, it fell under the FCC’s common carrier rules. This created a clear line of regulatory distinction between the services provided over the internet (website, applications, data services, etc.) and the means of data transmission.

While the internet was being born, cable TV started to work its way into American homes. When cable TV came into existence there was a debate regarding whether the FCC had the power to regulate it as a common carrier. One flaw of the 1934 Communications Act was that it had technical definitions on regulatory rules and cable TV was undefined in the Act.

Is Cable TV Common Carrier

While the debate raged, the FCC possessed wide latitude to regulate cable TV. That changed in a 1979 Supreme Court decision calling into question the “broadcasting language” under the common carrier definition of 1934. In the case FCC v. Midwest Video Corp., the court ruled the language “a person engaged in . . . broadcasting shall not . . . be deemed a common carrier.” applies to cable TV and therefore cable TV systems are not a common carrier.

At the time cable TV wires, transmissions, and channels were considered a luxury TV service. They were not delivering multiple services over a communications network like they are today. Therefore, the court simply looked at the content, “the broadcaster,” and decided the case on the broadcaster alone without separating content from the carrier.

The Early Internet was Title II

In the early 2000’s dial-up and DSL access to the internet was considered common carrier, also known as Tittle II under the 1996 Telecommunications Act. The technology sector in the U.S. had a massive innovation boom while the Internet had this classification.

As you would expect, when cable TV started delivering broadband internet, this posed a significant issue. Telecom companies had to provide access indiscriminately to their infrastructure, where cable TV companies did not. In fact, cable companies could use telecom infrastructure to deliver internet access if they were so inclined.

The FCC 2002 Misclassification

Of course, telecom companies and traditional Title II Internet service providers cried foul to the FCC. However, due to immense lobbying pressure from the cable TV industry, in 2002 the FCC declared cable modems as non-common carrier information services even though they provide the same exact function as dial-up and DSL modems. The chairman of the FCC at the time, Michael Powell, went on to head a lobbying firm for “. . . Comcast, Time Warner Cable, Charter, Cox, and other cable TV and broadband Internet providers.”

The FCC 2005 Misclassification

Rightfully folks in the tech industry and traditional common carrier ISPs freaked out. The FCC codified a situation where the big cable TV companies don’t have to share access their network as phone companies do. Their decision was held up in in the 2005 Supreme Court Case Brand X Internet Service vs. FCC. The high court deferred to the FCC due to the vagueness of the FCC policy definition.

Instead of the FCC correcting their glaring policy vagueness to justify why they broke with over nearly a century and a half of regulatory precedent, the FCC doubled down on their mistake. In 2005 the FCC again caved to the telecom lobby and reclassified dial-up and DSL Internet access as a non-common carrier information service.

ISPs become Information Services

2005 is the first year where ISPs are no longer obligated to adhere to common carrier principles. The FCC still understood the purpose of net neutrality and delivered a policy principle statement that stated:

- Consumers are entitled to access the lawful Internet content of their choice;

- Consumers are entitled to run applications and services of their choice, subject to the needs of law enforcement;

- Consumers are entitled to connect their choice of legal devices that do not harm the network; and

- Consumers are entitled to competition among network providers, application and service providers, and content providers.

ISPs start throttling customers

These were just guidelines and not official regulations. As such, ISPs immediately begin to take advantage of this lack of regulations. In 2007 the Associated Press found Comcast was throttling peer to peer file sharing technologies. The following year, the FCC filed a cease and desist order on Comcast for violating Net Neutrality.

Comcast ultimately sued the FCC and the cease and desist order was thrown out. The court found that the FCC did not have the authority to regulate non-common carrier information services when it comes to net neutrality. However, the FCC still had the power to designate ISPs as Title II services if they wish.

A Temporary Return to Net Neutrality 2011 – 2013

In 2010 the FCC tried again to rectify the mistakes they made in 2002 and 2005 by codifying the Open Internet Principles into an official regulation. This did provider some return to normalcy until 2014. That’s when Verizon won its case against the FCC.

Verizon’s suit challenged the FCC’s authority to implement it’s Open Internet Regulations on information services. The court agreed and essentially questioned why the FCC and net neutrality were in this policy predicament in the first place. If the FCC wanted to regulate ISPs as common carriers, why not designate them as such.

ISPs Return to Title II Designation

On February 26, 2015, after 4 million public comments in support. The FCC reclassified ISPs to their original Title II common carrier designation. This allowed the FCC to again regulate ISPs like a public utility and stop them from blocking, throttling and prioritizing content on their networks. This time, net neutrality was upheld in the courts.

Pai’s Arguments Against Net Neutrality

Trumps newly appointed FCC Chairman Ajit Pai wants to reset the clock back to 2005 and again declare ISPs information services. Now that we have a complete history of the rich history of net neutrality in the in the United States let’s take a look at his arguments.

Pai’s Skewed View of History

Before we look at his reasons for overturning net neutrality, let’s examine how he views this history. Looking at a fact sheet Pai recently released on the issue he states, “In 1996, President Clinton and a Republican Congress passed the Telecommunications Act of 1996 . . . This bipartisan approach was tremendously successful. The private sector invested about $1.5 trillion, connecting hundreds of millions of Americans.”

I agree that there has been undeniable innovation when it comes to the internet. However, Pai doesn’t recognize that before and after the 1996 Telecommunications Act, the entire internet was classified as a Title II common carrier and adhered to the rules of net neutrality.

According to the FCC’s documentation in 1997 100% of internet users were using a Title II designated ISP. In 2000, only 6% of internet users were using cable internet, which did not fall under net neutrality. In fact, a majority of internet users were not using cable internet when FCC removed the Title II designation from all ISPs in 2005. The massive surge of internet usage happened under a Tittle II regulated internet.

Bandwidth Increases Under Net Neutrality

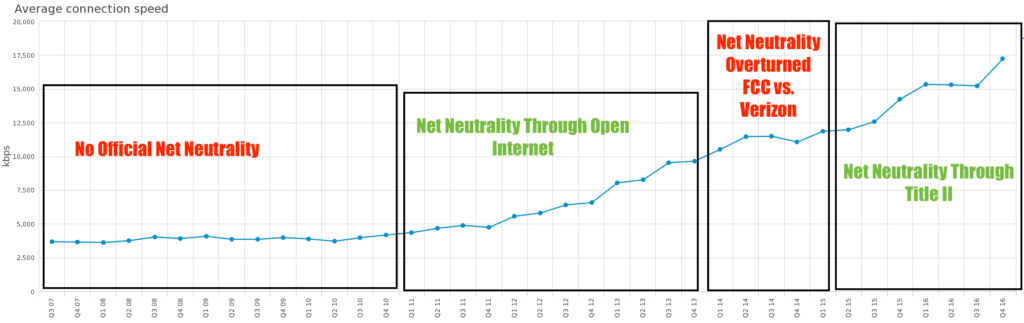

To see how the Internet performs under a net neutrality regulated internet, one only needs to examine data from Akamai. Akamai started studying the actual internet speed of every country in the world in 2007. Below is a chart using their data.

Pai loves to claim that net neutrality and Title II have killed innovation and infrastructure development. However, the data tells a different story. As history shows, ISPs weren’t fully considered an information service until the end of 2005. Internet speeds then were averaging just above 3 Mbps. Akamai shows that in the middle of 2007 the U.S was averaging about 3.7 Mbps.

The FCC officially adopted open Internet rules to enforce net neutrality at the end of 2010. At the time U.S. Internet users were being supplied with only 4.2 Mbps. Speeds nearly flatlined when ISPs were not under net neutrality regulations. However, under net neutrality, speeds more than doubled to nearly 10 Mbps by the end of 2013.

However, the Courts ruled against the FCC’s ability to enforce their Open Internet regulations over information services (non-Title II). With no net neutrality rules in place, America’s internet went from 10.5 Mbps to only 11.8 Mbps.

Since Wheeler’s FCC designated ISPs as Title 2, average internet speeds in the U.S. hit a 17.8 Mbps by the end of 2016. There is nothing in the bandwidth speed data that shows net neutrality hurts innovation. In fact, it is quite the opposite. It helps.

Why Pai’s Plan is Bad for Bandwidth

This is likely to due to anti-competitive behavior on the ISPs part when they aren’t being regulated. When ISPs have unlimited power over the communications infrastructure, they begin to hamper innovation by blocking and throttling applications, websites, and content that threatens their subsidiaries. There is plenty of evidence to show this.

When companies that deliver content, applications, and information aren’t hampered by bad ISP behavior, they innovate. Demand is created by these innovations and services. That demand for services then creates demand for bandwidth. ISPs, in turn, innovate to keep up with that demand.

Investment Hasn’t Declined Under Title II

Pai’s Claim the Title II classification hurt investment is demonstratively false. That can be inferred from the internet speed data above. However, there are plenty of hard numbers to disprove Pai’s intellectual dishonesty. Here are the facts:

- Comcast — the nation’s largest broadband provider — noted that in 2016 year over year “capital expenditures increased 7.5% to $9.1 billion.” 7.6 billion of that went to their communications division. That’s a 7.9% increase over the previous year

- The Merger of Charter and Time Warner cable saw increased investment over the total of both pre-merged companies pre-net neutrality years.

- Verizon has been loosing broadband customers for years, but their most recent capital expenditures have brought them even with their pre-net neutrality investment. There has been no massive decline.

Pai also claimed that infrastructure spending was shelved. This is likely due to a recent Divestment made by AT&T in 2015-2016. However, that was planned before the FCC declaring ISPs as a Title II entity. Pai consistently attempts to mislead the public using a report from economist Hal Singer. To be fair to Hal, he seems to honestly support the “no blocking” and “no throttling” tenants of Net Neutrality. However, he appears to be open to paid prioritization of data. Furthermore, some of his work in the past providing evidence against moving ISPs to Title II were partially funded by telecom lobbyists.

Hal Singer’s entire decrease hinges on AT&T. Removing the divestment that was planned before the Title II classification and investment is flat in his data. However, his numbers, vary greatly from what’s reported by U.S. Telecom for broadband investment. He claims 12 billion dollars less investment in 2014 and 14 billion dollars less investment in 2015.

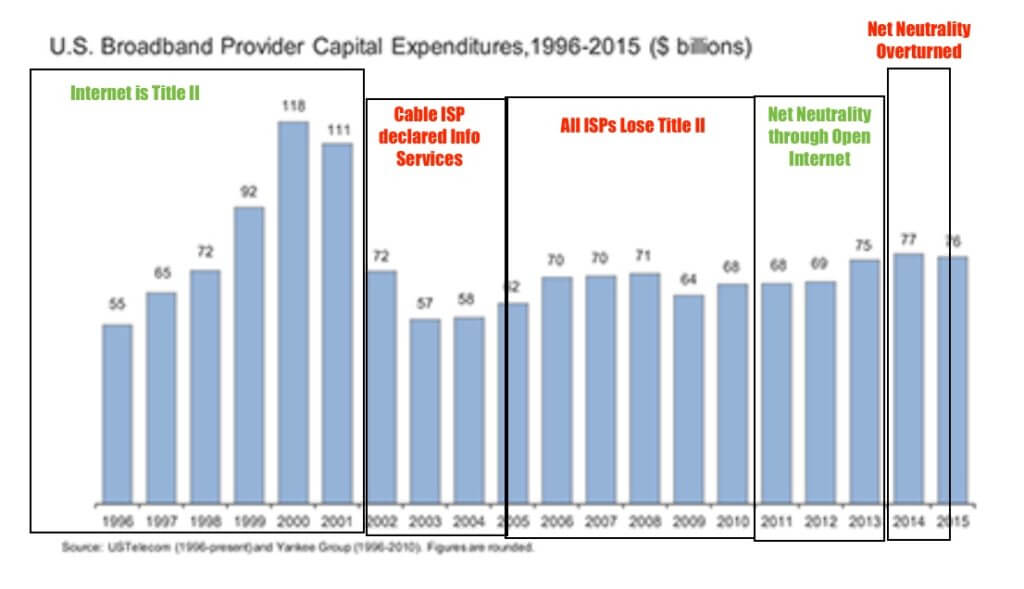

It looks like un-tampered data shows a massive investment spike under Title II regulated ISPs from 96-2002. In 2002 the first crack in Net Neutrality occurred declaring cable modems information services. Then, there is a massive decline in capital expenditures. There is a slight recovery in 2005. However, at the end of 2005, all ISPs were classified as information services, and investment went flat.

There was a slight uptick in investment during the open internet rules between 2011 and 2013. However, those were overturned as the Court ruled that the FCC can’t enforce open Internet rules on non-Title II information services. This is precisely why ISPs had to be reclassified as Title II, which was their original designation during massive infrastructure investment.

Jobs Did Not Decrease Under Title II

The numbers show that Ajit Pai is misleading the public when it comes to decreased infrastructure spending and innovation regarding ISPs being classified as Tittle II common carrier. However, he recently claimed “Thousands of good-paying jobs were lost due to lower infrastructure investment”

Well, let’s look at the annual 10-K SEC filings of Comcast, the largest ISP in the U.S. Here are the number of jobs at year end in their communications division (Excludes NBC Universal.)

- End of 2012 – 83,000

- End of 2013 – 83,000

- End of 2014 – 84,000

- End of 2015 – 88,000

- End of 2016 – 91,000

ISPs received their Title II designation in 2014. It looks like it started a hiring boom at Comcast. A skeptic may look at this and think; “Sure, but that’s just one company.”

Yes, but Comcast owns about one-third of all Internet connections in the U.S. and more than half of all broadband over 25 Mbps. However, if you look at AT&T, the largest Telecom ISP, you will see a growth of 25,000 jobs from 2014 – 2016. In the two years before being designated Title II, only 2000 jobs were created.

I admit it’s easy to cherry-pick statistics to try and prove a point. However, the evidence is staggering that ISPs have not suffered job loss from net neutrality. The internet fuels today’s IT sector, and the facts are more than half of the most in-demand jobs are in information technology.

Privacy

Pai’s most egregious twisting of reality comes in the form of claiming the following:

Americans’ online privacy was weakened because Title II completely stripped the FTC of its authority over broadband providers’ privacy and data security practices.

This is a staggering lie. Wheelers FCC was well aware of the FTC’s gap in privacy enforcement over ISPs. The FTC admitted this themselves in official documents. Are Technica reported:

The FTC’s privacy protection authority already stems from promises made by companies. “When companies tell consumers they will safeguard their personal information, the FTC can and does take law enforcement action to make sure that companies live up these promises,” the FTC says. But even in the privacy area, the FTC is limited by its own authority. “The FTC has repeatedly called for Congress to pass additional laws to strengthen the privacy and security protections provided by all companies,” FTC staff said last year.

When the FCC classified ISPs as Title II in 2015, the FCC crafted a more thorough privacy framework for ISPs. Republicans in Congress then created the enforcement gap by repealing the repealing the privacy framework before implementation. Furthermore, if Ajit Pai cared about your privacy, he would have voted for it when he had the chance.

Instead, Chairman Pai thinks it’s unfair for the FCC to regulate a company that’s industry is communications when media companies have more lax privacy rules at the FTC. If you want to know the myriad of reasons, this is just a shell game to completely deregulate ISPs, check out The Truth about your Online Privacy.

The Internet is a tool of the people and should belong to the people. We need to fight to protect it.

What You Can Do to Protect Net Neutrality

What Congress and Ajit Pai are doing to repeal a fair and open Internet while violating your privacy, is part of a plan crafted by ISP lobbyist. It will break with our countries tradition of common carrier communication and violate our privacy rights. Below are actions you can take to have the peoples voices heard.